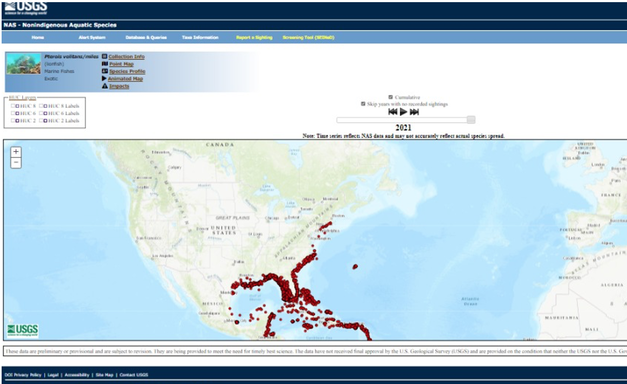

Photo by Ray Harrington on Unsplash Photo by Ray Harrington on Unsplash Lionfish, commonly known as zebrafish, turkey fish, or red firefish, are famous as ornamental aquamarine fish in the U.S. Lionfish is also the first invasive species of fish to establish in the Western Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean coastal waters, and in some parts of the Gulf of Mexico. Two of its indistinguishable species, Pterois volitans and Pterois miles, have been found, and scientists aren’t sure which was first to invade. The invasion started off as a humane act of dumping unwanted lionfish in coastal waters, where it turned out to be the worst man-made ecological disaster ever. In the marine ecosystem, this skilled invader out-breeds and out-competes native fish stock for food and space. The species is potentially harmful to the reef ecosystem. Ecological role of lionfish Lionfish are flamboyantly colorful with widely spaced red/brown stripes and have a long venomous spine. Lionfish can grow up to 20 inches in length and live from 5 to 15 years. They’re the top predators of the reef ecosystem of the Atlantic. Undulating slowly, these red-lionfish ambush their prey that are half of their size by fluttering their outer-stretched pectoral fins and slowly pursue and corner their prey into pockets of coral reef. Small fish do not recognize lionfish as predators. Instead, believes it to be a protector who’s here to shelter them with its long spines, fin rays, and pectoral fins. Lionfish are active nocturnal hunters. During the daytime, they’re found hovering above the reef head, where they gather in groups of up to ten or more. They consume over 50 fish and invertebrate species, some of which are recreationally, ecologically, and economically important. They exhibit a phenomenon called Aposmetism, meaning they show off as they can defend themselves to discourage their would-be predators from attacking them. Their 18 poisonous spines have venomous glands covered with the skin within two grooves. During a sting, the cover tears apart, and the spine is injected into the body of the predator, which delivers a deadly sting that can last for days. Venom is a complex protein that denatures as soon as it enters the victim. The experience is excruciatingly painful; symptoms include extreme sweating, pain, discomfort, and even paralysis to people and potential predators. That is why it is hard to catch and kill them. Flesh, however, isn’t poisonous and is a favorite delicacy. Native & non-native habitatLionfish are found in all types of marine habitats, from shallow reefs to deepwater and farther off the coast. Native to South Pacific and Indian Ocean (tropical and sub-tropical Indo-Pacific waters), lionfish is continually thriving and expanding its non-native range in the southeastern U.S. from Florida to North Carolina. In the native Indo-Pacific water, the burgeoning population is kept in check by predators and sometimes sharks. However, little is known about what eats them in their new habitat. Lionfish have no natural predators in the Western Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, or the Gulf of Mexico. Lionfish, itself, is an aggressive predator. Lionfish invasion in warm waters How did lionfish ended up and invaded the Atlantic? Well, there isn’t enough data. First sightings were reported along the coast of South Florida near Dania Beach in 1985. By the 2000s, species began to be reported off the Atlantic coasts of North and South Carolina and Georgia. As of 2010, it made its appearance in previously uninhabited waters such as the Gulf of Mexico and is now well-established throughout the western Atlantic. Scientists think they escaped during the 1992-Hurrican Andrew. Some others speculated that this invasion, like many others, was aided by humans. Lionfish gained massive popularity among aquarists, and that is why they were being harvested as juveniles for the aquamarine trade. However, as they mature, they’re hard to manage and thus released in the open waters. The unconscious dumping of aquarium lionfish into the Atlantic Ocean could be the reason for the uncontrolled invasion. Lionfish now own reefs, wrecks, and other habitat types. A recent study revealed that it can survive brackish coastal zones, river estuaries, and mangroves as well. Lionfish can tolerate a wide range of water temperatures and depths without any predator stress. They are biologically resistant to most diseases, and can survive up to 3 months in food-scarce areas without losing much of its body weight. Lionfish are a problem in Western Atlantic Ocean. They’re non-native to Atlantic waters and thus have very few natural predators. The population has astonishingly swelled in numbers in the past 15 years. In-depth warm waters are very crucial for the distribution and invasion of lionfish. Lionfish are prolific breeders; female lionfish matures in less than a year and produces two egg masses (each contains up to 25000 eggs) every four days in warm waters all year long, making it two million eggs a year. Lionfish larvae also have a high recruitment rate which becomes juvenile lionfish settled in a suitable environment. Most reef species breed only once a year, so lionfish have out-numbers native fish populations quickly. The predatory reed fish are indiscriminate eaters; they consume small crustaceans, fish, and other native species that fit their gaping mouth and stomach that can expand up to 30 times their normal size. It also feeds on commercially important fish species like yellowtail snapper, Nassau grouper, banded coral shrimp, parrotfish. Their voracious appetite is what is upsetting the economic and ecological balance of the reef ecosystem. Researchers found that a single lionfish residing on a coral reef can reduce native juvenile reef fish recruitment by 79 percent in just five weeks. Long-term effects on the fisheries industry are yet-to-be-determined. Also, scientists are not sure what eats a lionfish, but they expect that native species will learn how to avoid lionfish. Lionfish are also stressing out coral reefs. Coral reefs provide shelter and protection to juveniles of all marine species. It is also a source of as much as 80 percent of the Earth’s oxygen. Over 40 billion people relied on coral reefs to earn their livelihood through fishing and tourism. It is feared that lionfish would be responsible for the loss of beneficial algae-eating parrotfish, goatfish, surgeonfish, wrasses, and tangs from coral reefs, resulting in unchecked algal growth over the reed, which in turns, affects the health of coral reefs, previously struck by climate variability, pollution, ocean acidification, and other environmental stressors. What are scientists doing to get rid of lionfishThe population explosion has taken scientists by surprise. They are only beginning to understand the consequences of the lionfish invasion. What we know so far is native marine stocks are decimating as a direct result of lionfish invasion; commercial fisheries and lobster industries are crashing in places like Florida, and coral reefs are devastated. NOAA (National Center for Coastal Ocean Science), which first documented the establishment of Indo-Pacific lionfish in the Atlantic, is studying the lionfish invasion in collaborations with the REEF (Reef Environmental and Education Foundation) and the USGS (United States Geological Survey). According to NOAA researchers, marine invasive species are hard to eradicate once established. And lionfish have high fidelity to a location, meaning once settled, adults tend to stay there, reaching up to 200 adults per acre. The experts say that the population and invasion of lionfish, in the absence of natural predators, are bound to proliferate further south into South America in the coming years. Therefore, efforts are being centered on minimizing their impacts on marine resources. Even though no case of ciguatera poisoning has been reported to date, people still fear it. And that’s why the group launched an “Eat Lionfish” campaign to promote sustainable seafood choices through various media outlets. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission facilitates the removal or cull of any lionfish encountered; “Hunts and Derbies” are also organized at regular intervals in lionfish hotspots to keep the population in check. Catching and killing poisonous lionfish is not difficult with appropriate gear is not a difficult task anymore. Since they’re slow swimmers, they can be approached easily using multiple-barbed harpoons and spear guns. Fish may be dead, but poison isn’t, so care must be taken to avoid the puncture of the spine and entering of venom into flesh. Lionfish catch for public consumption has also bred a noticeable impact. We need a slight change of public perception that lionfish are poisonous. It isn’t. We’d spread the word among fishing communities and restaurants to add it to their catch list and menu, respectively. On the individual level, we can support these small businesses and industries to make up for their economic losses. As for marine fauna, we can only hope for them to adapt and survive! AuthorNida Riaz is a freelance blogger based in Pakistan. She started writing about her passion for the environment when the world came to a stop in early 2020.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

(833) CMS-LINE

(833) 267-5463 PO Box 13477 Mill Creek, Wa, 98082 © Conservation Made Simple. All rights reserved.

501(c)(3) Non-Profit, Tax ID#: 82-1646340 Copyright © 2021 Conservation Made Simple |