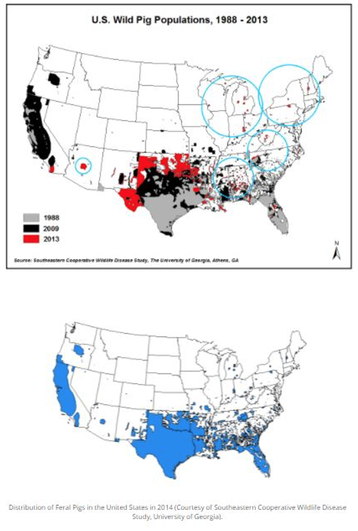

Photo by Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash Photo by Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash Boar, hog, pig, or swine; wild or feral! Whatever you call it, they all wallow in mud and destroy vegetation. Though they are all biological descendants of Sus scrofa, they can be differentiated depending on their genetics and environment. A pig is usually referred to as the barnyard variety; a boar is a non-castrated male that lives in the wild, a hog is simply a large pig or boar, and a piglet is a juvenile swine. And what about the wild and feral acronyms? All wild pigs are generally known as wild boars, however, escaped domesticated pigs are strictly called feral pigs or feral swine. They're not true boars as they belong to the subspecies Sus scrofa domesticus. Now, coming to the wild boars of the United States, they are a mixture of domestic breeds and European wild boars. When these two races mix, they produce what's called super-pigs. And the problem with these hybrids is you get all of the best benefits of each breed. Six million to nine million wild boars are wreaking havoc in at least 39 states and four Canadian provinces, half of them inflicting damages worth $400 million annually in Texas alone. They destroy recreational areas, frightening tourists in state and national parks occasionally and squeezing out other animals. Domestic pigs vs. wild boars Domestic pigs have been bred to be fertile year-round, have big litters, and grow large. Wild hogs are seldom as large as domestic pigs; adults weigh 150 to 200 pounds on average, with a few reaching more than 400 pounds. Males tend to be larger than females. Though farmers limit their diets in captivity, they can fatten up as they please when they're at liberty. Wild pigs have poor eyesight but excellent hearing, a strong sense of smell, detect odors up to seven miles away or 25 feet underground, and longer snouts useful for rooting. They can run at speeds of up to 30 miles per hour in a sprint. Most domestic pigs have sparse coats, but descendants of feral hogs grow thick spiky hair in cold environments. Wild hogs grow four curved "tusks" up to seven inches long, which self-sharpen from constant grinding. These are removed from domestics when they are born. Those who have reached sexual maturity develop a "shield" of dense tissue on their shoulders that hardens and thickens (up to two inches) with age; it protects them during fights. Wild hogs have no natural predators in America, and no legal poisons may be used to kill them. Their populations are growing alarming, with peaks in the breeding cycle during spring and fall. Sows (adult females) begin reproducing at 6 to 8 months of age and have two litters of four to eight piglets every 12 to 15 months for the rest of their lives, ranging from 4 to 8 years. Within two or three years, even porcine populations that had been decreased by 70% have recovered to full strength. Wild boars in Southeastern America Wild or domestic, hogs are not native to the United States. They were brought to Florida in the 1500s by Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto. Free-living domestic hogs provided an exotic food source for early explorers and settlers. The early settlers of Texas let pigs roam free until they were needed; some were never recovered. Many settlers abandoned their homesteads during wars or economic downturns, leaving the pigs to fend for themselves. Years later, in the early 1900s, Eurasian wild boars were brought to Texas and released for hunting. There are few purebred Eurasian wild boars today, but they have hybridized with free-roaming domestic animals and wild-adapted escapees. Today, hybrid populations have well-adapted and prospered throughout the wild pig’s range; in at least 45 states. According to a report published by Sports Illustrated, there’re over 8 million wild boars in the world, and about 2.6 million of these can proudly call themselves Texans. Wild hogs are a menace that cost over $1.5 billion in damages each year in the US. These invasive boars destroy crops, landscapes, and water supplies, munching trash, attacking dogs, and running into cars. Ever since the population has exploded in the 1980s, their popularity as game species, escape from hunting preserves, and illegal translocation to new locations encouraged their proliferation. The state-sponsored targeted hunting and killing whole sounders of feral pigs for the sole purpose of controlling pig populations also backfired. The more people liked hunting wild pigs, the more places they looked for them. This involved capturing free swine in areas where they already existed and releasing them in areas where they did not, thus establishing populations in new territories faster than the pigs could themselves. As a result, modern distribution maps depict isolated clusters throughout the United States. Even though the new hunting sites are fenced in, the pigs are notorious for digging their way out and escaping. Wild hogs breed too quickly that to eradicate a population, you must shoot 60 to 80 per cent of it each year. And sports hunting can only cut their numbers by 25 per cent. While many non-human predators, such as alligators, mountain lions, coyotes, and hawks, would enjoy some pig meat, there are too many pigs to go around. The invasion of pigs is partly attributable to the animals' intelligence, adaptability, and fertility. The cunning hogs tend to thrive in practically any environment, climate, or ecosystem—the distribution range from Southeastern Texas to Florida and as far north as Wisconsin and Canada. Since water is the only thing they can't live without (aside from food), they inhabit various habitats; bottomlands, rivers, streams, ponds, and even marshes and swamps. They prefer densely forested areas where they can hide and find shade. Because they lack sweat glands, they wallow in mud bogs during the hot months. They bury themselves in piles of grass and leaves when the weather turns cold. This not only cools them off but also coats them with mud, which keeps insects and the sun's rays off their bodies. They are surprisingly intelligent mammals that defy all attempts to capture or kill them. Those who have been unsuccessfully hunted are even more intelligent. And they are mostly nocturnal, one more reason they’re difficult to hunt. Wild hog populations were cultivated on ranches that sold hunting leases because hunters found them tricky prey. For example, the 3,000-acre ranch in McMullen County, owned by Lloyd Stewart's wife Susan since the mid-1900s, used to charge $150 to $300 for hog-hunting. "However, with the wild hogs becoming so common around the state, it's getting difficult to attract hunters. They don't want to pay to come to shoot them here," ranch manager Craig Oakes told Smithsonian Magazine. Trophy boars, any wild pig with tusks longer than three inches, are an exception. For a weekend hunt, these fetch around $700. Snaring hogs with a noose-like device hanging from a fence or tree is one approved technique for capturing them; however, this method has fewer supporters than trapping because other wildlife can be captured. Trappers bait a cage with food that is meant to attract wild hogs but no other animals. The trapdoor is left open for several days until the hogs become familiar with it. Once trapped, pigs are transported to a buying station, and from there, to a processing plant supervised by the United States Department of Agriculture's inspectors. Most pork meat is exported to Europe and Southeast Asia, where wild boar is considered a delicacy. Threats posed by wild boars The invasion of wild boars is a crisis that we have largely brought on ourselves. Boars have been fattening up on our crops for years. Sprawling cities are pushing the species out of its shrinking native habitat and forcing it to coexist with us. Simultaneously, we tempted it with the tides of garbage and wasted food that piles around our cities. They are becoming more aggressive in search of food and water. Although their numbers are growing as they move to cities, the shift is making them, and us, sick. According to a USDA spokesperson, these wild omnivores are responsible for an estimated $2.5 billion worth of damage each year, primarily by ploughing through crops, rooting plants, competing with and attacking native wildlife out of bogs, lakes, riversides, and forests. Wild pigs are opportunistic omnivores. With wild boars around your fields, whole fields of rice, wheat, corn, sugarcane, soybeans, sorghum, potatoes, melons, and other seasonal fruits, nuts, grass, hay, and everything they found appetizing will be devoured or decimated. They can root native vegetation and seedling as deep as three feet with their extra-long snouts. Thereby disrupting the entire ecosystem and making it simpler for invasive plants to establish themselves. Farmers who are growing corn have noticed that the hogs go down the rows and extract seeds one by one during the night. Some farmers in the US have taken so many blows to high-value crops that they've shifted to lower-value crops like cotton, which pigs find less attractive. And these are just a few of the issues that wild hogs cause in rural areas. Hogs scrape away the soil, muddy streams, and other water supplies, perhaps killing fish. The wild boars take any food left out for livestock and, on rare occasions, devour the livestock itself, particularly lambs and calves. They also consume nests of ground-nesting birds, carrion, deer, and quail, as well as the eggs of endangered sea turtles if the opportunity is presented. They're making themselves at home in parks, destroying historical places, tearing up golf courses and athletic fields, and contaminating water supplies throughout the US. They treat lawns and gardens as if they were salad bars, and they get into fights with household pets. Wild boars use fences as rub posts and cause significant structural damages. These are considered “the most destructive invasive species in the US.” Wild hogs are potential disease carriers due to their susceptibility to parasites and infections. A pig can be infected with at least 30 viral and bacterial diseases and nearly 40 parasites. Cholera, tuberculosis, Hepatitis E, Influenza A, swine brucellosis, and pseudorabies are the most concerning because of how easily they can be transmitted to domestic pigs and their threat to the pork industry and human health. Control and eradication programs for wild swine The programs include trapping, shooting, running with dogs, and hunting with the aid of bait. Due to a high reproductive rate and a lack of natural predators, wild boars are quickly becoming a huge nuisance problem in the United States, causing millions of dollars in damage to crops, pastures, forests, and wildlife. Without strong and consistent enforcement of local and state wildlife laws and regulations, wild pigs will continue to establish themselves in natural ecosystems throughout the country. That is why the USDA has spent so much money to keep the swine at bay. They previously assisted in funding control efforts in less densely populated states. Officials used corral-style traps to capture as many individuals of a sounder (a group of hogs) as possible and then euthanize the animals. According to the USDA, Idaho, New York, Maryland, and New Jersey are now pig-free. Iowa, Minnesota, Washington, and Wisconsin are also on the verge of success. Here are the things you can do to reduce this threat:

AuthorNida Riaz is a freelance blogger based in Pakistan. She started writing about her passion for the environment when the world came to a stop in early 2020.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

(833) CMS-LINE

(833) 267-5463 PO Box 13477 Mill Creek, Wa, 98082 © Conservation Made Simple. All rights reserved.

501(c)(3) Non-Profit, Tax ID#: 82-1646340 Copyright © 2021 Conservation Made Simple |